We're in a metabolic health crisis. Over four billion people are predicted to be overweight or have obesity by 2035 if current trends in global health continue [1]. Our lifestyles are higher in stress and sedentary time than ever, leading many of us to choose ultra-processed, highly palatable foods as a means to save time.

While we may not be able to change every single thing about our lifestyles, bringing small, sustainable dietary changes into our everyday lives can have big impacts on our metabolic health.

Why is nutrition important for metabolic health?

Nutrition is the most significant pillar for improving metabolic health as the foods we eat directly impact our cholesterol, blood pressure, waist circumference, and of course, blood sugar.

Highly palatable, processed foods lead to blood sugar spikes that signal the body to release insulin, a hormone that helps to keep blood sugar stable.

Occasional surges in blood sugar and insulin aren’t a cause for concern, as the body is equipped to handle these changes under normal, “healthy” conditions.

But consistent blood sugar fluctuations that result from poor dietary patterns can lead to insulin resistance, a condition where your body’s cells stop responding to insulin. Insulin resistance paves the way for hormonal imbalances, weight gain, and other metabolic conditions like type 2 diabetes.

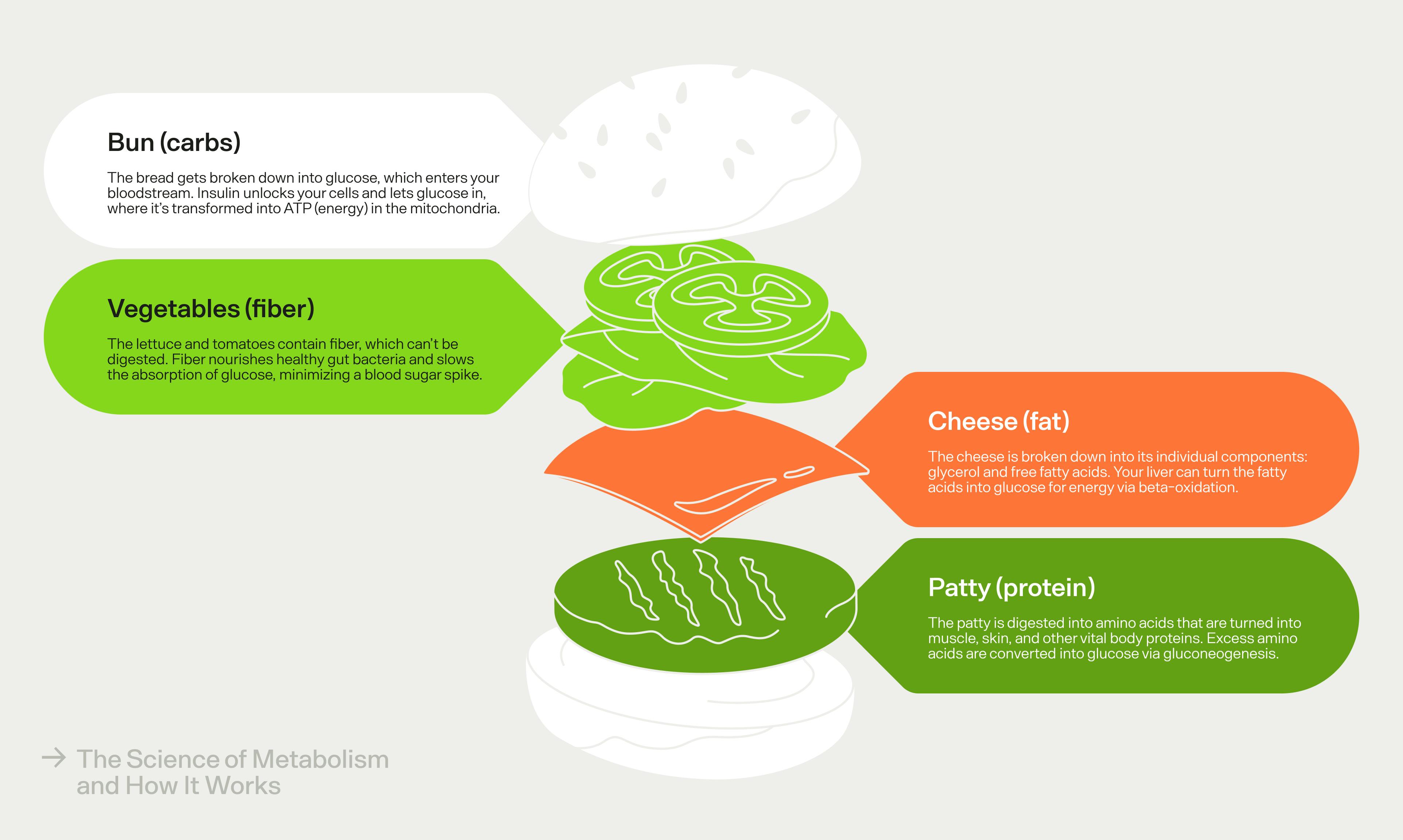

How your body processes different macronutrients.

Everything you need to know about macronutrients

Carbohydrates, protein, and fat are the three primary macronutrients. Each serves a different set of functions and supplies energy to the body in different ways.

Each macronutrient has a different effect on blood sugar. These effects may be altered depending on how much of a certain macronutrient we eat and whether we eat that macronutrient with other nutrients.

Here, we dive into how each macronutrient impacts blood sugar and share strategies for building meals that support metabolic health.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates fall into two categories: simple carbohydrates (i.e., “simple sugars”) and complex carbohydrates.

All carbohydrates — whether from a sweet potato or a candy bar — break down into glucose, the body’s preferred source of fuel. But that doesn’t mean all carbs are created equal.

Simple carbohydrates are made of shorter chains of sugars and are quicker to digest. These carbohydrates don’t keep us as full and satisfied as complex carbohydrates and often lead to rapid rises and subsequent crashes in blood sugar if eaten on their own.

While some simple carbs have health benefits — like honey, which is rich in anti-inflammatory polyphenols — the majority of the simple carbs in the standard American diet are found in ultra-processed foods (UPFs) like sugar-sweetened beverages (soda, coffee drinks, energy drinks, etc.), candy bars, and sweetened breakfast cereals [2].

We may feel tired, lethargic, and even hungry shortly after eating simple carbohydrates, leading us to reach for more of these foods to bring our blood sugar levels back to normal, only to perpetuate a vicious cycle of blood sugar spikes and crashes.

Complex carbohydrates are made of long chains of sugar and are slower to digest. A key component of complex carbohydrates is fiber: a type of carbohydrate that goes undigested in the body and doesn’t provide calories as a result. Research shows that soluble fiber — which turns into a gel-like substance during digestion — may help blunt blood sugar spikes and can also lower blood cholesterol levels by reducing the absorption of cholesterol in the blood [3, 4]. Fiber also helps to regulate the gut microbiome and feed beneficial gut bacteria [5].

Eating fiber with carbs can help blunt your glucose response.

Complex carbohydrates — like berries, sweet potatoes, steel-cut oats, and legumes — have a lower glycemic index (GI), meaning that they have a smaller effect on blood sugar levels compared to high-GI foods like soda, pastries, and refined carbohydrates. Eating too many high-GI foods over time can impair insulin sensitivity, leading to insulin resistance [6].

Carbs often get a bad rap, but improving metabolic health and preventing insulin resistance does not require a low-carb approach. Our brain and other vital organs need glucose to function so much that the body will create glucose from non-carbohydrate sources like amino acids if we’re not getting enough in our diet (through a process called gluconeogenesis).

Rather than eliminating carbohydrates:

- Focus on fiber-rich sources of complex carbohydrates like fruits, vegetables, starches (potatoes, squash, beets, parsnips, etc.), beans, legumes, and whole grains, all of which support balanced blood sugar levels and promote a healthy gut.

- Aim to reduce your intake of simple sugars from ultra-processed foods like sugary beverages and refined grains.

- Practice a sustainable, balanced approach to eating that incorporates your favorite foods (even high GI foods) using glucose-friendly practices, like giving your carbs a buddy, eating vegetables first, walking after meals, or eating smaller portions.

Protein

Protein is a key component of skeletal muscle mass and plays a role in a number of bodily functions, including:

- providing structure for bones, tendons, ligaments, cartilage, skin, and muscles

- supporting tissue repair and wound healing; assisting in the production of certain hormones like insulin

- making antibodies that protect from infection

Protein is the most satiating macronutrient, meaning it fills us up more than carbohydrates and fats.

Protein also has a GI of zero — meaning it doesn’t spike glucose in healthy individuals with adequate insulin.

When paired with resistance training, adequate protein intake can support the growth of new muscle tissue. While resistance training alone can lead to improved glycemic control, research suggests that muscle mass is associated with insulin sensitivity, independent of weight status [7]. Muscle mass may help to regulate energy intake through feedback signaling between fat-free mass and parts of the brain that control appetite, making weight loss easier [8].

Aim to prioritize lean proteins like lean ground beef (roughly 90-93% lean), turkey, chicken, fish (like shrimp, tuna, or salmon), plain Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, eggs, edamame, lentils, and whey protein powder at every meal and snack. For people who are overweight or have obesity, approximately 1.0 to 1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day is recommended.

Fat

Dietary fat is the most energy-dense macronutrient with 9 calories per gram (compared to 4 calories per gram of protein and carbohydrates), but we know that dietary fat does not inherently cause fat gain.

Fat helps the body produce certain hormones, absorb fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), support cell membranes, cushion organs, and store energy. Dietary fat also helps to blunt blood sugar spikes and makes our meals more satisfying.

Fats are categorized by their chemical structure:

- trans fats

- saturated fats

- unsaturated fats — including monounsaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats (omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids)

Similar to carbs, not all fats are created equal. For example, artificial trans fats formed during partial hydrogenation can raise LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels and increase the risk of heart attack and stroke, while omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to be protective of heart health [9].

Research suggests that increased intakes of polyunsaturated fatty acids relative to saturated fats are associated with decreased fat mass, decreased insulin resistance, and increased insulin secretion [10].

Cold-water fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, tuna, and sardines and nuts and seeds like flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts are excellent sources of omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 fatty acids are a powerful micronutrient that can help lower triglyceride levels, reduce inflammation, and improve insulin sensitivity [11]. They’ve even been shown to decrease waist circumference in individuals with polycystic ovary syndrome, a reproductive condition with key metabolic components [12].

Adding healthy fats like olive oil, avocado oil, coconut oil, avocadoes, seeds, nuts, and nut butters to lower-energy foods like vegetables and fruits can make them more enjoyable, increase absorption of important fat-soluble vitamins, blunt glucose spikes, and support satiety. You might derive more enjoyment from homemade meals, experience fewer cravings, and reduce snacking as a result.

Why micronutrients are important for metabolic health

Micronutrients are nutrients that the body needs in smaller amounts, like vitamins and minerals. There are nearly 30 micronutrients that the body cannot produce that we need to get from outside sources–like our diet [13].

While we need micronutrients in smaller amounts, failing to get essential vitamins and minerals may guarantee disease.

Eating a diet that’s diverse is the best way to cover your micronutrient bases. In the U.S., foods like ceral, bread, milk, iodized salt, and more are often enriched and fortified with essential nutrients, makingnutrient deficiencies rare.

With the exception of some groups — like vegans and vegetarians, those who are trying to conceive or are pregnant or breastfeeding, and individuals with gastrointestinal disorders — individuals should get all of their essential nutrients from plenty of fruits, vegetables, complex carbohydrates, healthy fats, and quality proteins from animal and plant sources. Fruits and vegetables in particular are filled with phytonutrients, powerful plant compounds that have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [14].

6 essential micronutrients to get in your diet

Here are examples of key micronutrients that are beneficial for combating chronic inflammation and for supporting metabolic health:

- Magnesium plays a role in energy metabolism and insulin sensitivity, and has been shown to support heart health. Magnesium is also associated with lower levels of low-grade inflammation, a condition associated with heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes [15]. Dark leafy greens, pumpkin seeds, cashews, almonds, black beans, edamame, peanut butter, and dark chocolate are all rich in magnesium.

- Anthocyanins are plant compounds that may reduce the risk of certain cancers, Type 2 diabetes, and obesity [16]. Foods that are rich in anthocyanins include blue and purple produce like blueberries, beets, and cabbage.

- Vitamin D promotes bone health, aids glucose and insulin control, and supports immune function [17]. Vitamin D deficiencies have been associated with metabolic conditions like obesity, Type II diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [18]. Egg yolks, mushrooms, organ meats, and white beans are good food sources of vitamin D, in addition to sun exposure.

- Curcumin has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties that fight oxidative stress [19]. Reducing inflammation and oxidative stress is key for reversing insulin resistance [20]. Turmeric and dishes like curry that use turmeric as a main ingredient are high in curcumin.

- Selenium helps to reduce oxidative stress that contributes to inflammation and helps to increase insulin sensitivity in muscle and fat [21]. Selenium also plays a crucial role in the function of the thyroid, a gland that helps to govern metabolism. Food sources include Brazil nuts (just two contain the dietary reference intake for selenium), yellow tuna, halibut, shrimp, sardines, turkey, and steak.

- Omega-3 fatty acids protect a range of metabolic parameters including lowering LDL-cholesterol and having anti-inflammatory properties. Food sources include flaxseed, chia seeds, walnuts, salmon, mackerel, sardines, trout, and herring.

What about supplements? We may not derive the same nutrition when we isolate foods in supplement form and we may lose out on the other benefits of consuming a diverse diet — like increased satiety and satisfaction, better gut health, and improved insulin sensitivity.

This is because foods are packaged with nutrients that work synergistically in the body to increase their absorption through what’s called the “food matrix.” For example, an egg yolk is naturally packaged with fats that help with the absorption of another micronutrient in eggs called choline.

Although a food-first approach is key, certain individuals like vegans or vegetarians, those who are pregnant or breastfeeding, and those with chronic gastrointestinal disease can benefit from supplementation that seeks to add to their diet rather than replace nutrient-rich foods.

4 practical tips to eat a metabolically healthy diet

Here are four key dietary strategies to consider to improve your metabolic health.

1. Build a metabolically healthy plate.

- Focus on colorful plates with plenty of lean proteins, fibrous vegetables, complex carbohydrates, and enough healthy fat to keep you satisfied. Aim for ¼ plate lean protein (~4-6 oz. to start and up to 8 oz.), ½ plate non-starchy vegetables (~2 cups), and ¼ plate complex carbohydrates (~1 serving, for example 1 medium sweet potato) to start and tweak based on your individual needs.

- Avoid “naked carbs” and pair carbohydrates with a source of protein, healthy fats, and/or fiber for better blood sugar control and reduced cravings.

- Aim to increase your intake of complex carbohydrates and reduce your intake of refined sugar and ultra-processed foods without being overly restrictive.

- Avoid deeming foods as “off limits” as this typically leads to feelings of deprivation, which may motivate us to abandon our healthy habits [22].

2. Eat at optimal times.

- Focus on eating patterns that align with the body’s circadian rhythm to improve insulin sensitivity, such as eating breakfast within 1-2 hours of waking and consuming dinner ~2-3 hours before bedtime [23].

- Consider eating a protein-forward breakfast, which can support balanced blood sugar levels throughout the day and into the evening [24].

- For those who practice intermittent fasting, consider following an early time-restricted feeding (eTRF) window where you eat earlier in the day then fast (versus vice versa). eTRF may better align with the body’s internal clock, reduce late-night eating, and support weight loss goals [25].

3. Focus on nutrient density rather than calories.

- Focusing solely on calories may produce weight loss without benefiting health and may not be a sustainable approach.

- Prioritizing nutrient-dense foods like lean proteins, fiber, and healthy fats improves metabolic outcomes and can lead to a natural calorie deficit that supports weight loss as a result.

4. Experiment with glucose-balancing hacks.

- Take a brisk walk after meals which regulates blood sugar by supplying energy in the form of glucose to working muscles [26].

- Play around with sequential eating: eat foods that take longer to digest first — like veggies, protein, and healthy fats — and save your carbs for last to blunt blood sugar response.

- Cook and cool your rice and potatoes to create resistant starch, a type of prebiotic that helps feed beneficial gut bacteria and improves insulin sensitivity.

- See how your body responds to certain foods by wearing a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), and getting real-time data to best support your metabolic health.

Key takeaways

- Nutrition is the most significant pillar for metabolic health and reframing your view of nutrition can have a substantial impact on your metabolic health, weight goals, and relationship with food.

- Understanding the role of key macro- and micronutrients can help you make informed and personalized nutrition choices that benefit your health without promoting feelings of restriction or deprivation.

- Small, specific changes that you’re able to maintain over the long-term add up more than unrealistic goals you can’t sustain. Focus on just one habit at a time like “adding 1 cup of vegetables to lunch” or “walking for five minutes after dinner.”

- Wearing a CGM can provide real-time insights into how your body responds to certain foods, allowing you to observe trends over time and make small changes in the moment.

Ali McGowan is a Registered Dietitian with her Master’s degree in Nutrition, Interventions, Communication, and Behavior Change from the Friedman School at Tufts University and currently works in the field of obesity. Ali is passionate about the spread of sound nutrition and health information and seeks to explain both the “what” and the “how” behind key concepts to help individuals make empowered and personalized health decisions. When she’s not working, you can find her spending time in nature, cooking, or finding joy in movement. Follow her on Instagram @sproutoutloud.

References:

- https://www.worldobesity.org/news/economic-impact-of-overweight-and-obesity-to-surpass-4-trillion-by-2035

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6225430/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1663443/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6566984/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8153313/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2654909/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7483278/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35797356/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8413259/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/3/615

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5872768/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5461594/

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/micronutrients-have-major-impact-on-health

- https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/46/3/1029/3039477?login=false

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2992198/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5613902/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4499086/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6513299/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5664031/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2319417017301506?via%3Dihub

- https://www.scielo.br/j/bjps/a/GZsSGmGVwZYrt9CVCfvShZt/?format=pdf&lang=en

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5918520/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5483233/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36615743/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8143522/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8912639/