Recall a time you ate a carb-heavy meal, like pasta with sauce, and how you felt afterward. The pasta probably left you feeling sluggish and tired, maybe unfocused.

Now, think about a time you ate a colorful, leafy salad and how you felt after. Probably pretty different, right? While these examples are both extreme, the point is that they’re both made up of different kinds of carbs — and have vastly different effects on blood sugar and mood.

Two ways to measure the impact carbohydrates have on our blood sugar levels are glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL). Both have to do with carbohydrates because they measure glucose, but their difference isn’t quite clear by their names. We can distinguish the two in order to better understand carbohydrates and how our bodies respond to them.

What is glycemic index?

Glycemic index is a measure of how quickly a carb-containing food is broken down and absorbed into the bloodstream. The time it takes for a food to be absorbed is measured on a scale from 0 to 100.

For example, glucose is a carbohydrate in its purest form, and is absorbed the fastest — so it’s given the highest value of 100.

High-GI foods cause a rapid spike in blood glucose and quick insulin response. On the other end of the spectrum, low-GI foods contain very few carbohydrates and are digested slower. Pure fats, such as olive and vegetable oils, and proteins (like animal meat) don’t contain carbohydrates — they have GI values of 0 because they don’t affect blood sugar.

In other words, it’s only giving you a fraction of the bigger picture — a fast rise in your glucose levels doesn’t necessarily mean they skyrocket into an unhealthy range.

In order to know how much a food affects blood sugar levels, we use glycemic load.

What is glycemic load?

Glycemic load is the same as GI but it takes the amount of carbohydrates into account. In other words, it’s GI but factors in size, or portion, of carbs you’re eating.

GL is calculated by multiplying the GI value by the amount of carbs in a serving of food and then dividing that number by 100. So as an equation:

GL = GI x grams of carbohydrate / 100

Foods can be categorized as low GL (0-10), moderate GL (11-19), or high GL (>20) [1].

Glycemic index vs. glycemic load: is one better than the other?

Glycemic load is a better tool to measure a food’s impact on blood glucose and insulin response than glycemic index alone because it also considers the amount of carbohydrate in a portion [2].

For example, watermelon has a GI value of 76, which is high on the scale — which may lead you to think that it’ll cause a major spike [3]. But one serving of watermelon (1 cup of cubed fruit) only has 11 grams of carbs because it’s mostly water. In other words, it’s absorbed quickly into your bloodstream (so it has a high GI), but it doesn’t have a lot of carbs (so the GL is low).

If we calculate the GL (GL = (76 x 11 grams carbohydrate) / 100), we get a value of 8, making it a low-GL food. So eating a serving of watermelon isn’t actually going to have a big effect on your glucose levels.

Think of it like throwing rocks in a pond. It's not just the type of rock that affects the splash but how hard you throw it and how big it is. Similarly, a low-GI food may only have a small effect on blood sugar, but eating a lot of it will have a greater effect on blood sugar.

Considering both the quality and quantity of the carbohydrate, glycemic load is a slightly better indicator of how your body will process glucose than glycemic index alone.

The relationship between glycemic response and metabolic health

Glucose is the body’s preferred energy source. When we eat food with carbs, insulin is released to help glucose absorption. When insulin binds to cell receptors, glucose can easily move from the bloodstream to the cell and be used as energy to power cellular activities and body functions.

The effect on glycemic response

Glycemic response can show the effect foods and meals have on blood sugar levels.

Foods with a high GI value will cause a rapid glycemic response, where blood sugar levels rise and crash rapidly. In contrast, foods with a low GI value will have a smaller effect on blood sugar levels.

Eating high-GI foods or low-GI foods in large portions occasionally is OK, as the body can respond to large amounts of sugar periodically.

The effect on insulin sensitivity

However, eating too many high-GI foods over time can impair insulin sensitivity [4]. If insulin is constantly being released to absorb large amounts of glucose, it loses its effectiveness.

Over time, more insulin is required to absorb blood sugar, leading to prolonged high blood sugar and deteriorating insulin effectiveness.

When cells become desensitized to excess insulin and stop responding properly, this can lead to insulin resistance, which has both short-term and long-term consequences. Immediate effects include blood sugar levels remaining high, leading to side effects such as mood swings, tiredness, headaches, and skin breakouts [5]. Elevated blood sugar over time increases risk for Type 2 diabetes, weight gain, heart disease, and kidney damage [6].

How can you track your glucose response to foods?

While GI and GL values can be helpful in understanding the impact of foods you eat on your glucose levels, it’s not practical to measure the GI/GL of everything you plan on eating. They’re also both imperfect tools because they fail to capture unique, individual differences in glycemic response.

Unlike a picture, movies tell a whole story by providing a narrative, context, and plenty of details. And like a movie, a CGM can give a more holistic view of your body’s unique metabolic response than determining a GI or GL value.

The value of continuous glucose monitoring

CGMs give an abundance of information, such as average glucose and the amount of time spent in the optimal range, that illustrates our body’s individual response to food.

Instead of a snapshot, a CGM gives real-time glucose data to show you exactly how your body responds to a food or meal. And since carbohydrates are rarely eaten in isolation, a CGM allows you to see the effect of other factors, such as food pairings, cooking methods, and meal timings on your blood sugar.

Eating a low-glycemic diet: where to start

Monitoring blood sugar over time can reveal how stable your glucose levels are throughout the day. There are a number of benefits associated with stabilizing blood sugar, such as reversing insulin resistance, regulating hormones, and maintaining weight, and research suggests an easy way to actualize these benefits is via a low-glycemic diet [7].

1. Pay attention to carb amount and quality

Balancing both portion size and carbohydrate quality will help you build meals that won’t send blood sugar levels skyrocketing. Eating small amounts of high-GI foods can minimize blood sugar spikes.

You also don’t have to cut carbohydrates out completely. A low-glycemic diet can still contain high-quality carbohydrates. Both a whole apple and apple juice have carbohydrates, but an apple has a GI value of 35 whereas apple juice has a GI value of 41.

Since they both have carbohydrates, they will increase blood sugar, but the soluble fiber in the peel of the apple will diminish the glucose response. Other fiber-friendly foods such as berries, lentils, and avocados have been shown to reverse insulin resistance, an essential step in stabilizing blood sugar and improving insulin sensitivity.

2. Focus on protein and fat

In addition to eating foods with soluble fiber, another strategy is pairing a carbohydrate with a fat or protein, two nutrients that help to slow glucose absorption, prevent rapid spikes, and improve satiety. For example, overnight oats are a low-glycemic breakfast meal consisting of whole rolled oats, a splash of whole milk, flax seeds, and a scoop of peanut butter. So even though there are carbohydrates, the combination of fiber, fat, and protein will produce a slower glucose response.

3. Avoid processed foods

Sticking to whole, unprocessed foods is another way to minimize a glycemic response. Processed foods are typically packaged, shelf-stable foods loaded with salt, sugar, and fat. These ingredients tend to tax our metabolism, making it difficult to naturally digest and absorb them. Opting for minimally processed foods like colorful non-starchy vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats, is better for your blood sugar and metabolism.

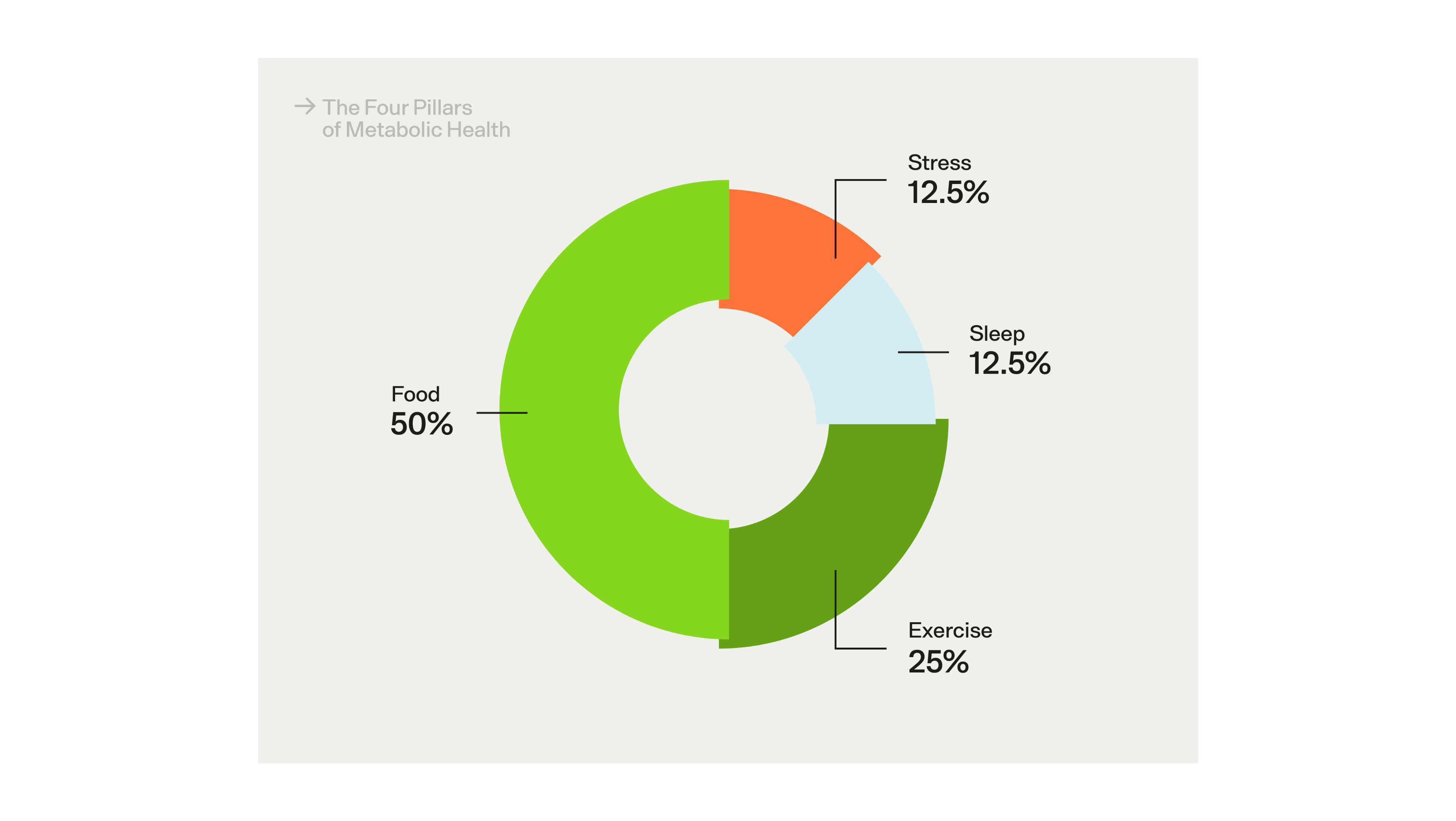

The Four Pillars of Metabolic Health — i.e., the factors that have the greatest impact on metabolic health.

The effects of lifestyle on insulin sensitivity and glycemic response

While diet is the most important part of maintaining stable blood glucose levels throughout the day, it's not the only factor. At Veri, we've distilled existing research into Four Pillars of Metabolic Health — the most important areas of your life to focus on if you're trying to prevent insulin resistance, metabolic health dysfunction, and keep your energy levels and hormones in balance. In addition to diet, here are some tips to keep in mind:

- Exercise can help improve insulin sensitivity and glycemic response. Even just taking a quick walk after a meal can reduce your postprandial glucose levels by up to 39%.

- Sleep is a crucial part of optimal metabolic health. Getting bad sleep — i.e., irregular sleep/wake times and sleep deficiency — can actual worsen your insulin sensitivity, leading to more extreme glucose responses to the foods you eat.

- Stress is a healthy and natural part of life, but chronic stress levels — where cortisol remains high in your body — can actually increase insulin resistance and lead to poor glycemic response, weight gain, and gradual metabolic dysfunction.

Key takeaways

Glycemic index and glycemic load are useful tools for creating grocery lists and meal preparation, but a CGM ultimately provides the data to support long-term habits. Seeing positive changes in your body and metabolic health in real time will show what dietary and lifestyle choices are optimal for you and your blood sugar.

- Use a CGM to get the full story about your body’s unique glycemic response to different types of foods and meals.

- Aim for low-GI foods by swapping out refined carbs for whole unprocessed carbohydrates like whole-kernel bread, brown rice, barley, and quinoa, and stick to suggested serving sizes.

- Incorporate fibrous foods such as whole grains, fruits, and non-starchy colorful vegetables into your meals to slow your blood sugar spike.

- Pair a carbohydrate with a protein and fat to ebb the glycemic response after a meal.

- Avoid the metabolic consequences of processed foods and select whole, minimally processed foods.

References:

- https://www.diabetes.co.uk/diet/glycemic-load.html

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/glycemic-index-and-glycemic-load-for-100-foods

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2654909/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7352659/

- https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/complications/hypers

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430900/

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/glycemic-index-and-glycemic-load-for-100-foods