It used to be the most important meal of the day, but now, breakfast is being seen as unnecessary, if not detrimental, to our health. The data aren’t quite conclusive in that regard, and we’ve seen a back-and-forth of media coverage regarding the benefits or risks of skipping breakfast.

For instance, some recent studies show that skipping breakfast is associated with an increased risk for diabetes or an 87% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality [1, 2].

On the other hand, a lot of recent data indicate that people who practice intermittent fasting (IF) or time-restricted feeding (TRF) might receive health benefits compared to those who don’t do either. In my experience, most people who practice IF/TRF choose to skip breakfast.

This presents us with a bit of a paradox that can be easily explained. The studies showing negative effects of “breakfast skipping” are all association studies — i.e., people report whether they regularly eat or skip breakfast, and those responses are tied to a specific health outcome. Not the most robust of research designs.

But breakfast skipping and fasting aren’t the topics of this article, but rather, whether or not you should exercise before or after breakfast (assuming you’re eating it).

The science behind working out fasted vs. fed

Benefits of Fed Workouts

Isn’t food good for performance? Why would anyone choose to exercise without something to give them energy?

These are all valid arguments and critiques against the “fasted exercise” argument.

For the most part, having something to eat (primarily carbohydrates) before exercise or high-intensity activity is shown to benefit performance compared to doing the same activity fasted [3]. Whether it’s long-duration aerobic endurance exercise, team sports (intermittent activity), or high-intensity interval training, performance gets a boost from having a bit of fuel in the tank. Hell, even pretending to consume carbohydrates by rinsing your mouth with a carbohydrate-containing rinse (and not swallowing) can enhance performance [4].

And even when pre-exercise feeding shows no benefits above and beyond fasted exercise, fasting never produces better performance compared to fed exercise; period.

Benefits of Fasted Workouts

But those who advocate fasted exercise cite reasons other than performance for their attraction to this practice. For one, the enjoyment and comfort of exercise seem to be better for some on an empty stomach (myself included). There’s less to worry about in terms of GI distress, bathroom breaks, or heartburn if you haven’t eaten anything before your 10-mile run.

The more frequently cited benefit is that of a metabolic adaptive advantage with fasted exercise.

Fasted workout benefits for insulin sensitivity

Another benefit of fasted exercise might come in the form of improved insulin sensitivity. Insulin sensitivity refers to our ability to increase glucose uptake into our muscles in response to a rise in blood glucose (this is partly mediated by insulin). In someone who is insulin insensitive (insulin resistant; i.e., someone with Type 2 diabetes, a.k.a. T2D), there is reduced uptake of glucose into cells. Basically, insulin fails to do its job effectively.

Insulin insensitivity is linked to a slew of metabolic conditions, including obesity, T2D, and even Alzheimer’s disease. Therefore, strategies to enhance insulin sensitivity in those prone to disease are a priority for health researchers.

Nutrient-exercise timing

Studies have investigated the ability of fasted vs. fed exercise to enhance insulin sensitivity, among other metabolic biomarkers, in an attempt to settle the debate about when the “optimal” time to exercise is, and whether or not you should work out with your gas tank on E.

Published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, the study, titled “Lipid metabolism links nutrient-exercise timing to insulin sensitivity in men classified as overweight or obese” investigated a concept known as “nutrient-exercise timing" [5].

Essentially, this concept relates to the time frame in which nutrients are consumed in relation to exercise. In particular, whether you exercise while in the fasted or the fed state, and how this influences your response to physical activity and your adaptation to it.

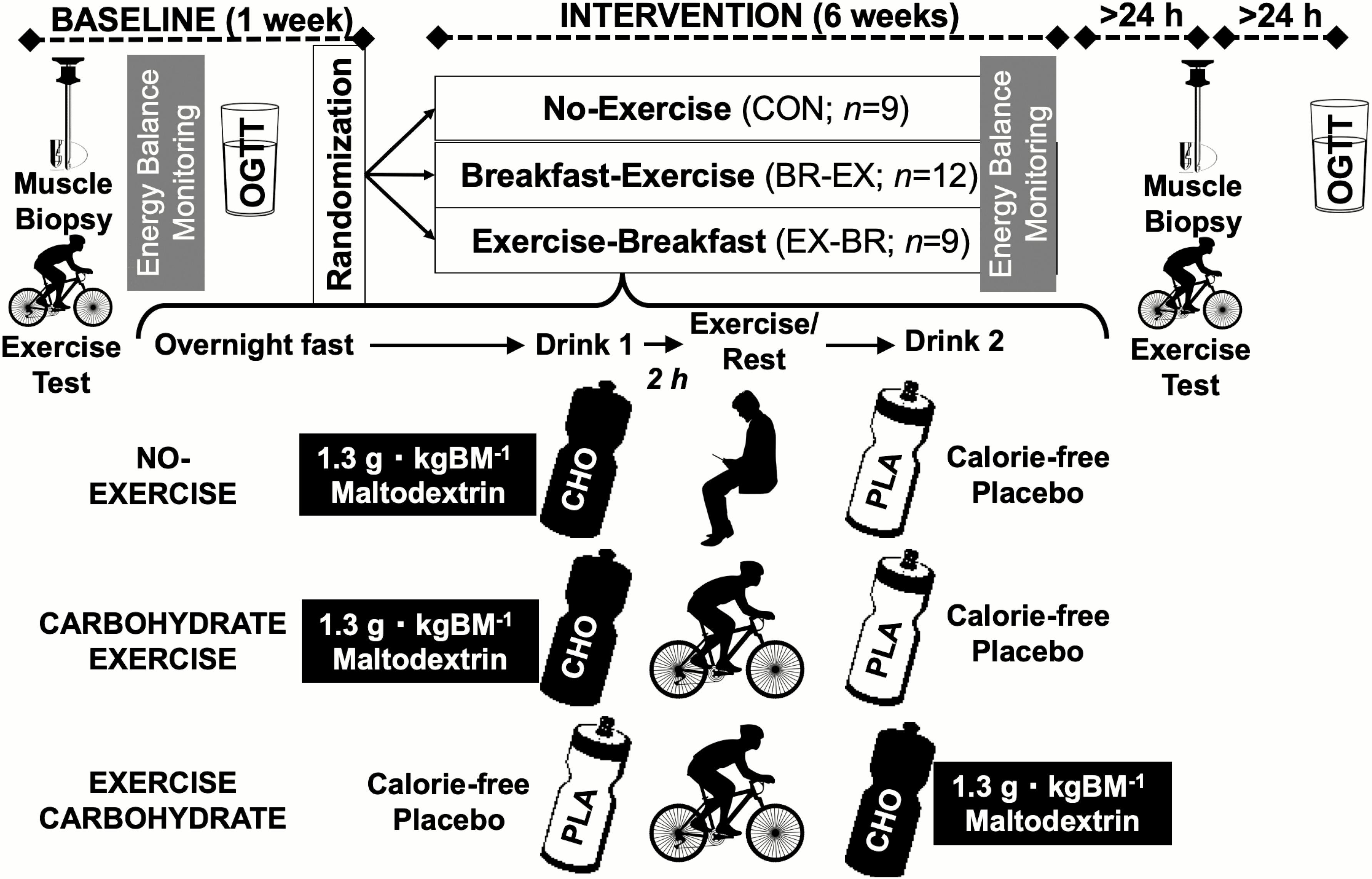

This study investigated nutrient-exercise timing using two study arms; one involving an acute exercise session and another utilizing a 6-week exercise training intervention.

Protocol schematic for the Training Study. Courtesy of Edinburgh, Bradley, et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 105, Issue 3, March 2020, Pages 660–676.

Study design

Acute study

12 men completed two conditions in a randomized crossover order. In one condition, they completed a 60-minute session of moderate intensity (65% V02 max) cycling followed by a high-carb breakfast.

In the other condition, the order was revered — breakfast then exercise (90 minutes later).

Measures: Expired gas samples during exercise to determine what amount of fat and carbohydrates they were utilizing, blood samples to test for glucose, glycerol, free fatty acids, and insulin, muscle biopsies for skeletal muscle triglyceride content, glycogen, and protein expression of genes related to metabolism.

Main outcome: Comparison of lipid (fat) utilization during exercise when fasted vs. fed.

Chronic study

30 men were randomized into a control (no exercise) group, fed-exercise training group, or fasted-exercise training group. The fed group received a carbohydrate-containing beverage 2 hours before exercise, and the fasted group consumed a placebo (no carbs or calories) before exercise and had the drink after.

Measures: Pre- and post-training oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) to test insulin sensitivity, muscle biopsy for muscle lipid composition, metabolic enzyme activity, and proteins involved in glucose transport/insulin signaling.

Main outcome: The change in the glucose/insulin response to OGTT (an index of oral glucose insulin sensitivity) between fasted and fed exercise groups.

Results

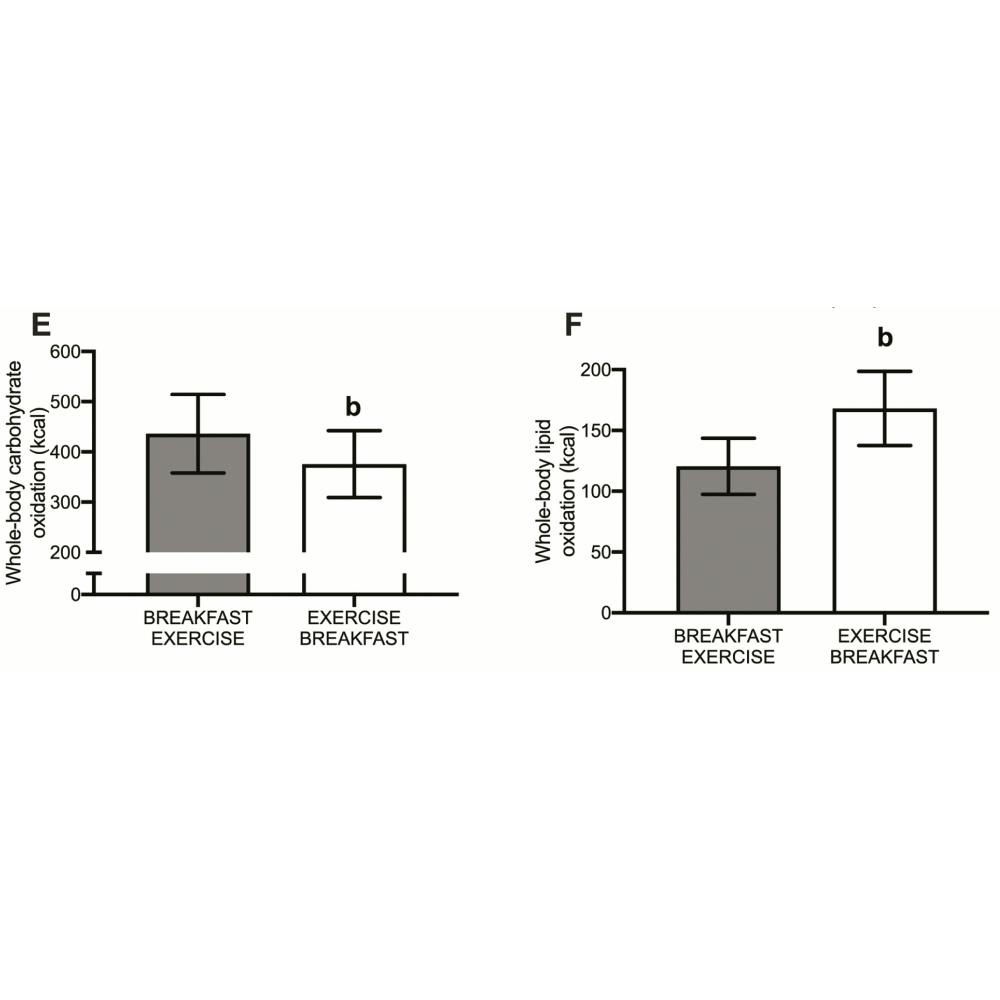

Compared to fed exercise, fasted exercise resulted in an increase in whole-body lipid utilization.

During the exercise bout, the group who consumed breakfast first had an increased respiratory exchange ratio (RER), indicating they were utilizing more carbohydrates for energy. On the other hand, the fasted exercise group was burning a greater amount of fat throughout the exercise bout.

Looking at the muscle biopsy samples revealed that the fasted exercise group had much lower muscle triglyceride content after exercise — a result that aligns with the findings above.

Carbohydrate (left) and lipid (right) oxidation during exercise. Courtesy of Edinburgh, Bradley, et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 105, Issue 3, March 2020, Pages 660–676.

In the chronic study, similar findings were observed.

The group who completed the exercise training in a fasted state experienced a 2-fold increase in their lipid utilization during exercise, which was maintained throughout the entire 6-week trial. They reduced their “reliance” on carbohydrates and burned more fat during exercise.

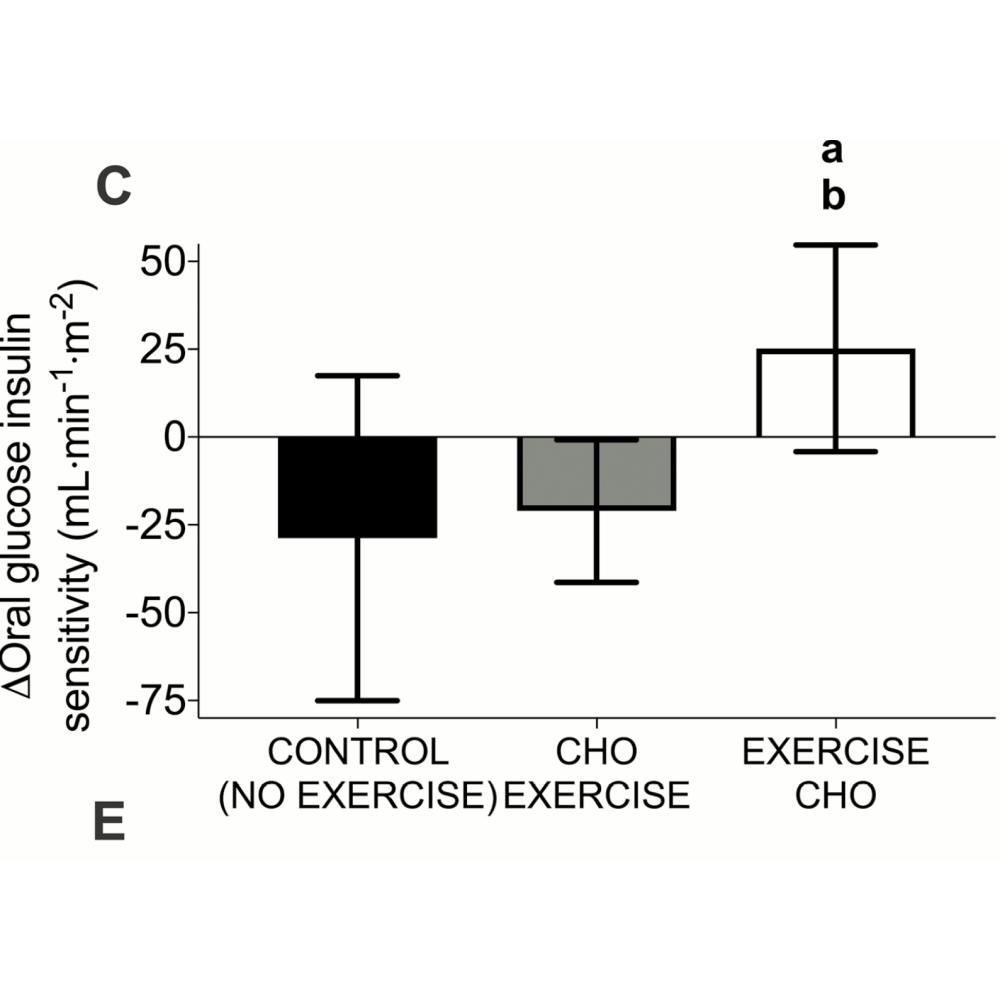

The fasted exercise training group also experienced an increase in their insulin sensitivity after 6 weeks — their insulin response to the OGTT was lower — meaning they needed less insulin to take up the same amount of glucose (basically, insulin “worked better”).

Insulin sensitivity index change in response to exercise training. Courtesy of Edinburgh, Bradley, et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 105, Issue 3, March 2020, Pages 660–676.

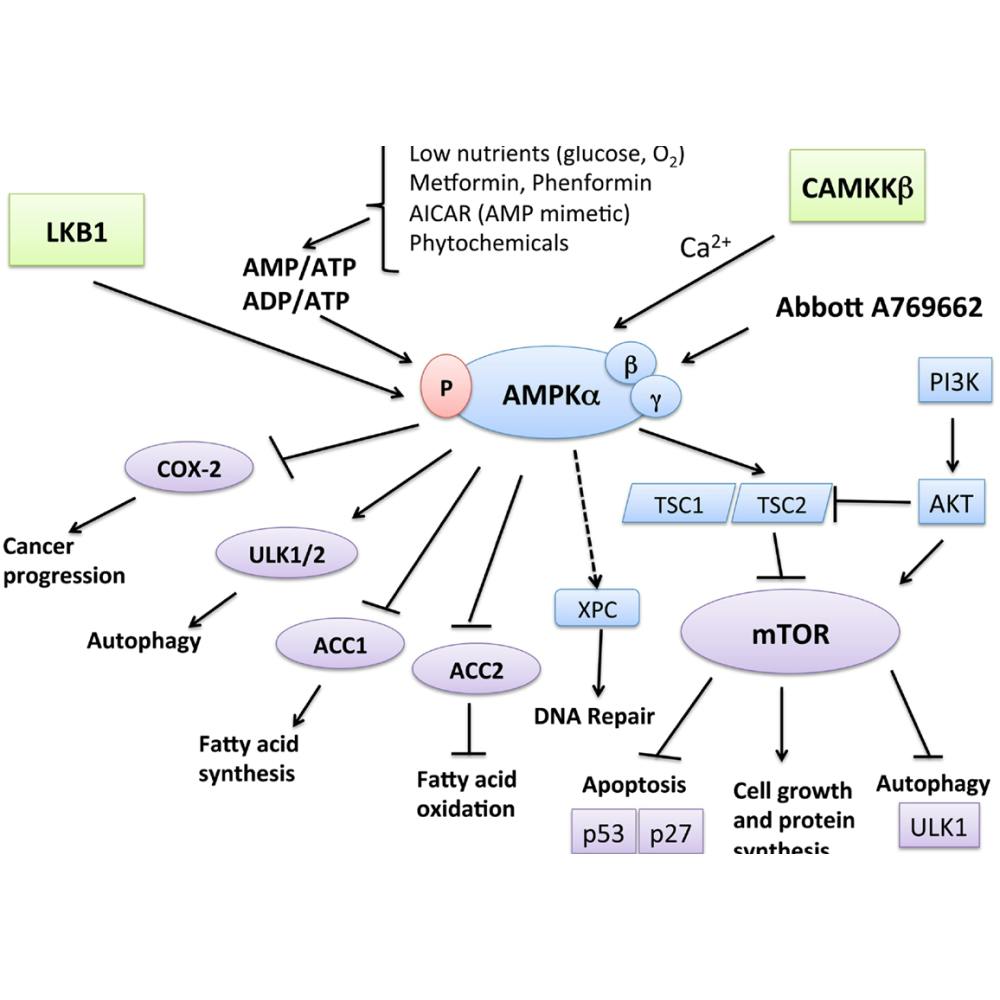

There were also some interesting changes at the cellular level. Specifically, a protein known as AMP kinase (AMPK) was increased 3-fold in the fasted-exercise group. AMPK is known as a cellular “nutrient sensor” which is able to upregulate gene expression by detecting whether our body is “high energy” (i.e. fed) or “low energy” (i.e., fasted).

AMPK plays a big role in the regulation of fatty acid oxidation, the building of new mitochondria, and glucose uptake (all things that contribute to insulin sensitivity). Thus, the response of AMPK to fasted exercise likely explains many of the beneficial metabolic effects observed in this study and others.

Study key takeaways

- A single bout of fasted exercise increased lipid utilization.

- Fasted exercise training increased fat utilization 2-fold.

- Fasted training improved insulin sensitivity.

- Fasted training increases energy sensing (AMPK) and glucose transport (GLUT4) proteins.

The AMPK pathway. Courtesy of Kim I and He Y-Y (2013) — Targeting the AMP-activated protein kinase for cancer prevention and therapy. Front. Oncol. 3:175. [6]

I’m not sure if the findings from this study are that surprising — the fact that fat utilization increases when you exercise while fasted isn’t exactly novel. However, what makes this study interesting is the fact that the population was overweight/obese men, not lean, healthy, young adult men (“the usual subjects”). Thus, it has implications that can apply clinically and perhaps shed some light on strategies to improve individual health.

It’s a simple change to make — whether you’re doing it for reasons of personal preference, health, or longevity — that could perhaps have significant health effects over time.

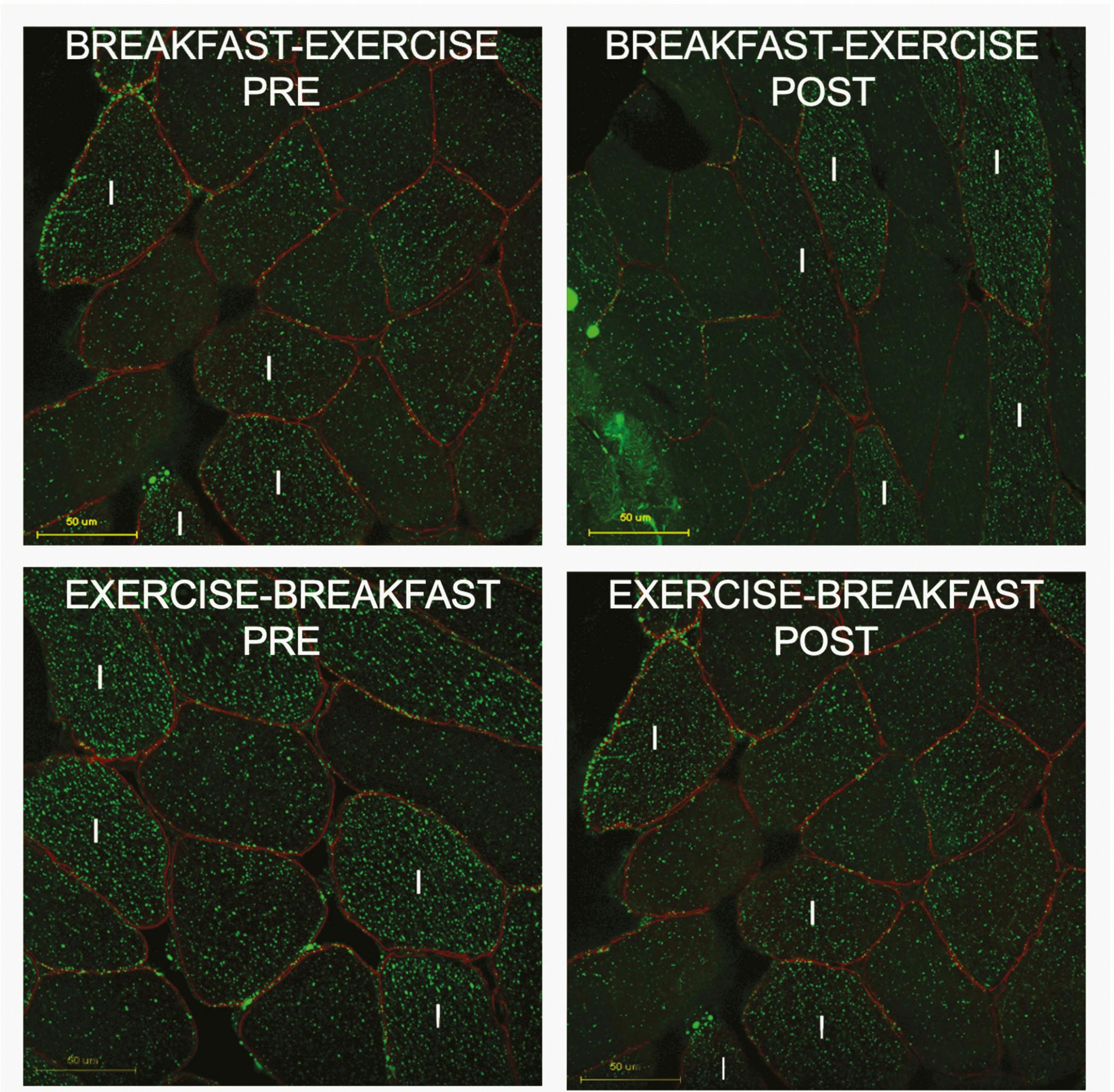

Courtesy of Edinburgh, Bradley, et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 105, Issue 3, March 2020, Pages 660–676.

More data continue to emerge on the importance of meal timing. We used to think that all that mattered was how much and what you ate (though these do matter considerably). Now, when you eat and when you eat in relation to things like exercise and sleep are known to play a huge role in health — a role larger than we once thought.

I’ve experimented with multiple different strategies to modulate my exercise performance and currently undergo most of my training (endurance running) in a fasted state. While I wouldn’t ever race or compete fasted, training fasted is more comfortable, sustainable, and actually leaves me feeling quite good. It’s something to get used to, however. The body can become adapted to most things and, when that happens, we are usually all the more stronger for it.

Brady Holmer has a Bachelor's degree in Exercise Science and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Applied Physiology and Kinesiology. His research interests include the effects of exercise and sleep on cardiovascular health. He is also a researcher at Examine.com and is an avid endurance athlete. Brady lives in Austin, Texas with his wife and dog.

- Substack: www.bradyholmer.substack.com

- Twitter: www.twitter.com/B_Holmer

- Website: www.bradyholmer.com

References:

- https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/149/1/106/5167902

- https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.065

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/sms.13054

- https://www.gssiweb.org/sports-science-exchange/article/sse-118-carbohydrate-mouth-rinse-performance-effects-and-mechanisms

- https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/105/3/660/5599745

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2013.00175/