When people think about exercise, they often associate it with weight loss or muscle gain.

But there are other impactful benefits of exercise — such as reversing or preventing insulin resistance, improving metabolic health, and even reducing the risk for coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes [1]. Research has shown that you can experience these benefits regardless of the type of exercise you engage in.

The most common types of exercise are:

- Aerobic exercises — i.e., exercises that use oxygen (think running, swimming, or biking).

- Resistance training, or weight lifting — a type of exercise that is normally done with equipment like dumbbells or resistance bands.

- HIIT (high-intensity interval training) — which is characterized by repeated, short periods of intense or anaerobic (without oxygen) movements, such as squat jumps, high knees, or burpees, with brief recovery periods.

Often, a person may do some combination of all three of these exercise types during the week. Some workouts, like metabolic conditioning, intentionally incorporate aspects of all three to target the way your body uses and stores energy.

But are there specific exercises, frequencies, and durations that you can focus on in order to get the most out of your workouts? Read on for our research-backed tips.

1. Walking

You don’t always have to lift weights or run several miles to make a substantial difference in the way your body regulates glucose levels. In fact, walking is one of the most effective things you can do for your metabolic health.

Other research in obese women found that walking 50-70 minutes 3 times per week for 12 weeks resulted in weight loss and improved insulin sensitivity [3].

Interestingly, even just standing up throughout the day can reduce your postprandial glucose levels by about 9.5 percent [4].

The takeaway to keep in mind is that living a sedentary life — i.e., where you’re sitting for most of the day — is linked with poor metabolic health, and any kind of movement you enjoy (even walking around your home after a meal for a few minutes if you’re short on time) is better than nothing.

What to do:

Within 2 hours of a meal, try getting at least 2 (but ideally 15-30) minutes of walking outside, every day. (If you do resistance training, try walking for longer sessions on days when you’re not lifting weights.) An easy way to get more walking into your life is to park your car a little farther away from a destination like a grocery store or a restaurant, or walk home (or walk to the next bus/train stop) if you live in a city.

2. Squats

Squats are a well-rounded exercise because they engage major muscle groups like your hip muscles, calves, hamstrings, obliques, and quadriceps — so you’re getting more bang for your buck. Squats also require core stabilization — another bonus.

Although research on squats and insulin resistance is limited, one study found that engaging in resistance or strength training exercises in general for less than one hour per week was associated with a lower risk of metabolic syndrome, independent of aerobic exercise [5]. Those who engaged in resistance exercise 2+ days per week and in aerobic exercise for 500+ minutes per week had a 17% lower risk of metabolic syndrome [6].

What to do:

Start by doing 8-10 squats until you can comfortably do 3 sets of 10. Repeat these 3 sets of 10 squats at least 2-3 times per week. After that, you can add weight (dumbbells or a weighted backpack), but be sure to have a foundation and proper form before adding on any extra weight.

To avoid knee injury, research suggests that you should take extra care if you’re in a narrow stance with your feet pointing out at a 42-degree angle, or a wide stance with your feet parallel (a 0-degree angle) [7]. After you feel comfortable, don’t be afraid to amp it up.

3. Swimming

Swimming is one of the best aerobic exercises you can do. Not only is it a full-body aerobic workout that can strengthen your heart, but it’s also low-impact (meaning easier on your joints than exercises like running) and can help you improve your flexibility.

Research also shows that swimming can improve your insulin sensitivity. One 2018 study performed on both healthy participants and individuals with metabolic syndrome found that a swimming routine that consisted of 4 sessions per week (at 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes respectively) for 3 months helped reduce HOMA-IR, which is an insulin resistance score [8].

What to do:

Start by incorporating 30-minute swimming sessions into your week and work your way up to an hour. You can mix one or two swimming sessions per week with walking, jogging, cycling, or other aerobic activities.

4. Burpees

Burpees combine a pushup and a jump in one movement. They’re a fantastic exercise to incorporate into a HIIT-style workout because they’re a full-body movement that engages multiple muscle groups and challenges both your flexibility and endurance.

One review looked at 50 studies that examined the effects of HIIT on markers of metabolic health including glucose regulation and insulin resistance [9]. In both groups, there was a reduction in insulin resistance after the HIIT workout. HbA1c levels, a measure of one’s average blood sugar (glucose), decreased by 0.19% and body weight decreased by 1.3 kg, compared to the control group. Participants at risk of or with type 2 diabetes had reductions in fasting glucose levels.

What to do:

Start by doing burpees for 30 seconds (making sure to give it your all) and resting for 30 seconds, and doing at least 3-5 sets. Keep doing this for about 10 minutes. If you want to switch things up, alternate burpees with exercises like mountain climbers, high knees, and jumping jacks. Repeat this HIIT-style workout 2-3 times per week, and gradually increase the time per workout to 20-30 minutes.

5. Hatha yoga

Yoga is a practice that is thousands of years old, but research has only recently focused on its effects on health. One of yoga’s best benefits for metabolic health is its ability to help you manage stress — scientists have found that just 8 weeks of yoga can help improve stress levels, which play an important role in glucose regulation [10].

Though more studies need to be done, some research has also found that yoga may improve your body’s ability to regulate glucose. One study had participants do a 60-minute yoga routine twice a week for 5 weeks, and revealed that postprandial glucose, fasting glucose, and HOMA-IR all decreased [11].

What to do:

The best way to do yoga if you’re a beginner is to take a class at a local studio. The instructor will be able to help you make adjustments to your form and posture — ensuring that you’re safely performing the exercises. If you’re at home, try a mix of standing postures (like swaying palm tree posture and triangle posture) along with seated twists, breathwork/meditation, and light stretching [12].

3 weekly exercise plans for insulin resistance and metabolic health

There's no one size fits all approach to what the best type of exercise is. There’s also no “best” time of day to work out. It depends on your lifestyle, what feels right for your body, and what you enjoy doing.

However, consistency is king — even if it’s just 30 minutes of your day. Studies suggest that practicing a combination of resistance and aerobic exercises is beneficial for your metabolic health [13]. In fact, it can improve your insulin sensitivity and reduce the risk of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and Type 2 diabetes.

Current guidelines for adults (ages 18 - 64) suggest that for substantial health benefits, adults should engage in:

- 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) to 300 minutes (5 hours) per week of moderate-intensity exercise, OR

- 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) to 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, OR

- an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity [14].

Additionally, adults should engage in muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or vigorous intensity that involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days a week.

Not everyone’s workout schedule is going to look the same, and your workout schedule may differ from week to week as well. Staying committed to your routine and repeatedly showing up for yourself and your health will be worth it.

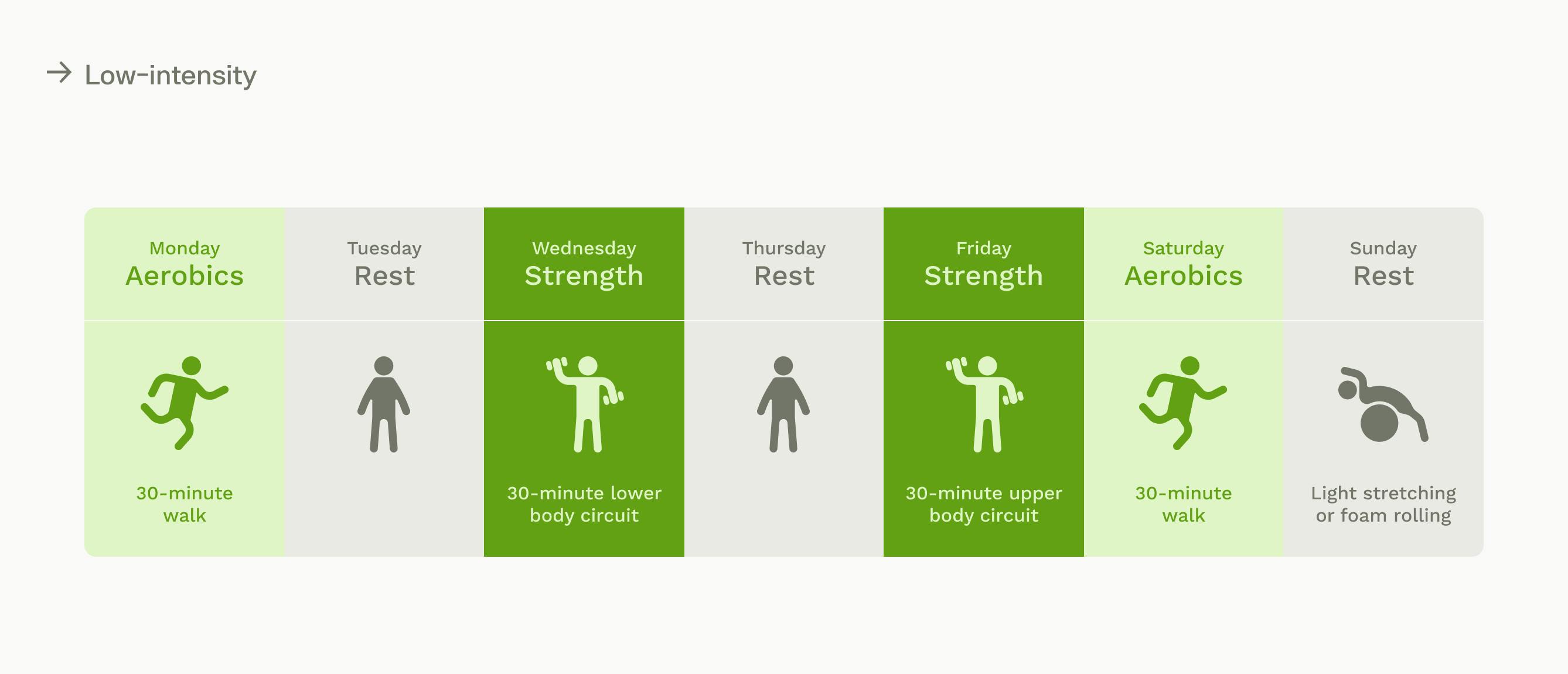

Here are examples of weekly workout routines according to intensity level:

This low-intensity workout routine is the perfect starting point if you're just easing back into an exercise plan.

Low-intensity workout

- MONDAY (AEROBICS): 30 minutes of walking or light jogging

- TUESDAY (REST)

- WEDNESDAY (STRENGTH): 30 minutes of a lower body circuit with bodyweight only (2 sets with 10 reps each of squats, forward lunges, side lunges, calf raises, step-ups)

- THURSDAY (REST)

- FRIDAY (STRENGTH): 30 minutes of an upper body circuit with bodyweight only (2 sets with 10 reps each of push-ups, crunches, shoulder taps, tricep dips, 30-second plank)

- SATURDAY (AEROBICS): 30 minutes of walking or light jogging

- SUNDAY (REST): 30 minutes of yoga (optional) or light stretching

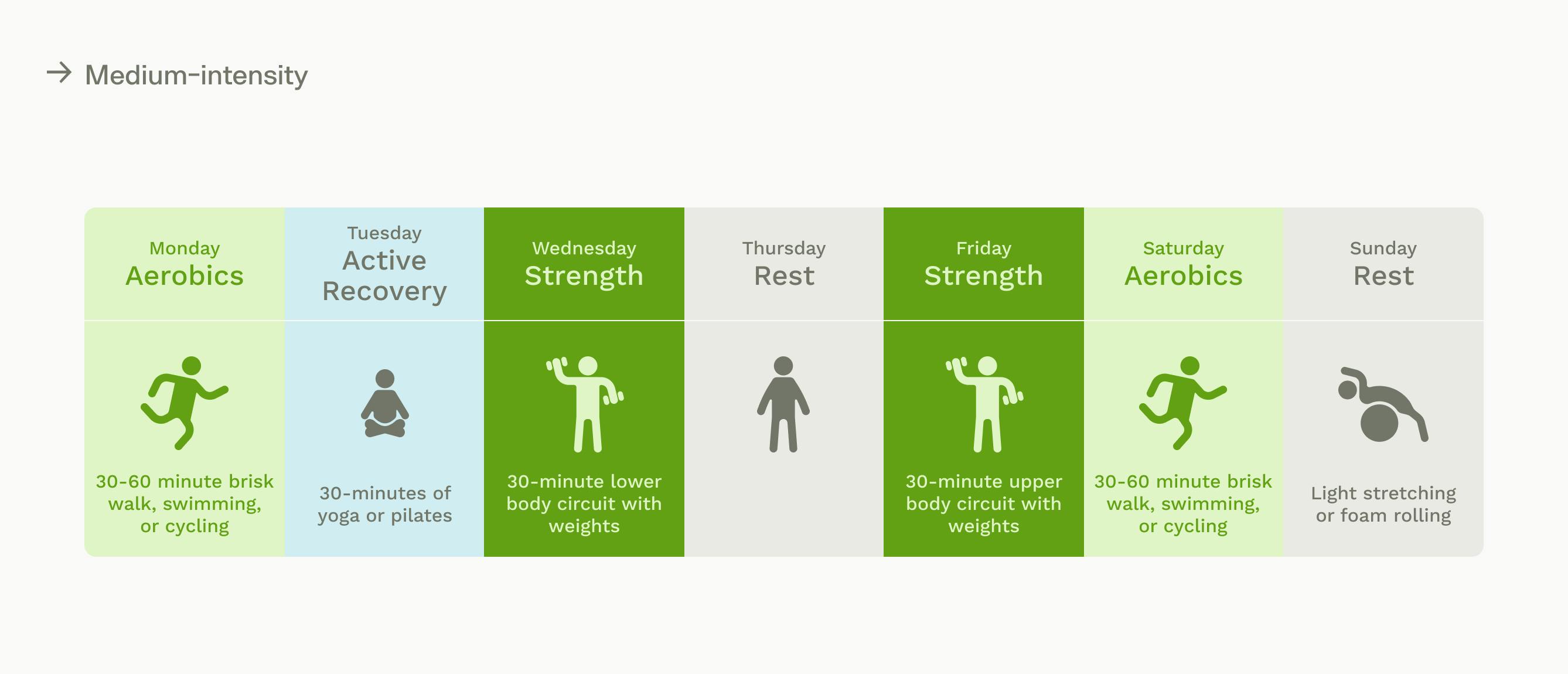

Once the low-intensity routine stops challenging you, it's time to move to a medium-intensity program.

Medium-intensity workout

- MONDAY (AEROBICS): 30-60 minutes of brisk walking, cycling, or swimming

- TUESDAY (ACTIVE RECOVERY): 30 minutes of active yoga (Vinyasa or Hatha yoga)

- WEDNESDAY (STRENGTH): 30 minutes of a lower body circuit with dumbbells (3 sets with 10 reps each of squats, forward lunges, side lunges, calf raises, step-ups)

- THURSDAY (REST)

- FRIDAY (STRENGTH): 30 minutes upper body circuit with dumbbells (3 sets with 10 reps each of push-ups on toes or knees, bent-over rows, overhead shoulder presses, overhead tricep extensions, 30-45-second plank)

- SATURDAY (AEROBICS): 30-60 minutes of brisk walking, cycling, or swimming

- SUNDAY (REST): 30 minutes yoga (optional) or light stretching

If you've been regularly active for a while, a vigorous-intensity workout routine may be perfect for you. If you experience joint pain, unusual aches that don't subside, or dizziness, dial back to a gentler workout.

Vigorous-intensity workout

- MONDAY (AEROBICS): 30 minutes of brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or running

- TUESDAY (STRENGTH): 30 minutes of a lower body circuit with moderate-to-heavy weights (3-4 sets with 10 reps each of narrow squats, wide-leg squats, hip thrusts, deadlifts, burpees)

- WEDNESDAY (HIIT): 30 minutes of HIIT — 30 seconds of exercise followed by 90 seconds of rest (mountain climbers, burpees, leg lifts, jumping jacks)

- THURSDAY (STRENGTH): 30 minutes upper body circuit with moderate-to-heavy weights (2 sets with 10 reps each of push-ups on toes or knees, bent-over rows, overhead shoulder presses, overhead tricep extensions, 30-45-second plank)

- FRIDAY (ACTIVE RECOVERY): 30 minutes of active yoga (Vinyasa or Hatha yoga)

- SATURDAY (AEROBICS): 30-60 minutes of brisk walking, running, swimming, or cycling

- SUNDAY (REST): 30 minutes of gentle yoga (optional), light stretching, and/or foam rolling

Does exercise cause a blood sugar spike?

While all exercise can improve insulin sensitivity can help reverse insulin resistance, if you use a CGM you may notice that your glucose levels spike temporarily after working out.

Exercise has short- and long-term effects on blood glucose. In the short term, exercise will increase the uptake of glucose by the muscles both during and after a workout [15]. As a result, glucose will leave the bloodstream faster — lowering your blood glucose levels. Your muscles will use this glucose for immediate energy and store the rest for later.

Interestingly, some higher-intensity workouts like HIIT, sprinting, or biking can actually cause your blood glucose to spike temporarily [16]. This is because your liver releases more glucose into the bloodstream so your muscles have enough energy to complete the challenging workout, which causes a spike. Don’t worry — this response is healthy and normal, and doesn’t contribute to insulin resistance.

Key takeaways

There are benefits to all types of exercise, so whether you enjoy HIIT, resistance training, or aerobic exercises, you’ll be taking strides toward improving your metabolic health — just remember to keep track of what your personal health goals are and focus on the workouts you enjoy doing.

- Set an alarm to move during prolonged sitting periods. Going for a quick 5-minute walk around the block is a great way to get some movement in, but even standing and stretching have an impact on your glucose levels — so try to take calls while standing or invest in a laptop riser for your desk.

- Ultimately, you want to enjoy your workout because the more joy you find in it, the more consistent you will be. However, don’t be afraid to switch up your routine or, better yet, mix in different types of exercises within a set workout. Add an aerobic finisher (i.e., a run or swim) to the end or beginning of a strength-based workout.

- Using health tools like a CGM can help you identify the effect of your workouts on your glucose levels throughout the day. If you use a CGM, you may notice that exercise can cause short-term spikes in your blood glucose levels. This is normal as your muscles need this extra glucose to use as energy during and after your workout session.

- Although exercise is an important component of your health, other factors such as nutrition, sleep, and stress play an important role as well.

References:

- https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-813

- https://www.hindawi.com/journals/scientifica/2016/4045717/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4241903/

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-022-01649-4

- https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(17)30167-2/fulltext

- https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(17)30167-2/fulltext

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6050697/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6307524/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26481101/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10615806.2017.1405261

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8798588/

- https://www.yogapedia.com/yoga-poses/swaying-palm-tree-pose/11/11410

- https://bmjopensem.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000143

- https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10683091/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3891224/