The average American adult consumes a staggering 17 teaspoons of added sugar per day [1]. That equates to 60 pounds of added sugar consumed annually — or six, 10-pound bowling balls.

Children, who are often the target of processed food marketing, face even worse statistics. Official guidelines advise that children should not exceed 6 teaspoons, yet many are keeping up with the adults, consuming 17-18 tablespoons daily — three times the recommended amount.

Regardless of age, our collective sugar intake far exceeds the recommended limits, contributing not only to weight gain but also causing issues with our metabolic health, immune function, mental health, and more.

What is added sugar?

Sugar is a sweet-tasting carbohydrate derived from various plants, often added to food and drinks for sweetness or preservation. However, not all sugars are created equal. They are typically categorized into two types: naturally occurring and added sugars. The concern lies with added sugars since their consumption has been linked to a rise in various health issues.

Naturally occurring sugars, found in fruits and dairy products, consist of simple sugars known as monosaccharides — individual sugar units such as glucose, fructose, and galactose. Imagine these sugars as the building blocks of sweetness, like individual letters forming words.

Moving beyond monosaccharides, disaccharides are when two sugar units join together. For instance, glucose combined with fructose creates sucrose, while the pairing of glucose and galactose results in lactose.

Expanding further, polysaccharides are multiple sugar units intertwined, producing complex structures such as starch, glycogen, or cellulose.

Refined or added sugars, used in convenience foods and sugary beverages, undergo processing steps such as the removal of fiber and crystallization for purity, altering their original form.

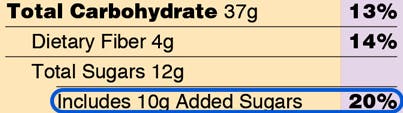

Common examples include table sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, and golden syrup. Picture these as rearranged puzzle pieces, different from those naturally occurring, which in turn have a different impact on the body’s function. These added sugars are in addition to naturally occurring sugars, as indicated on nutrition labels. These added sugars enhance the sweetness and palatability of foods and introduce empty calories—i.e., calories that lack nutritional value for your body and can leave you feeling hungrier and less satisfied than before.

Added sugars are included on nutrition labels under the nutrient section (Total Carbohydrate). The number of grams of added sugar listed here are per serving — meaning if that there are 3 servings per package for the example pictured here, there would be 30 grams of added sugars total.

Even "natural" sweeteners, like honey, maple syrup, and coconut sugar, fall into the added sugars category. Despite their wholesome image, these sweeteners still contribute to our overall sugar intake.

Surprising foods with hidden sugar

While the research shows we are all consuming too much sugar, most people aren’t exactly pouring the sweet stuff straight onto their food. The majority comes from processed and packaged foods, and often sugar can be hidden where you least expect it. In fact, manufacturers add sugar to 74% of packaged foods sold in supermarkets [3]. For instance:

- Soups and pasta sauces: Lots of unsuspecting quick meals and sauces contain added sugar.

- Nut butters: Even seemingly healthy options like nut butters contain a significant amount of refined sugar, potentially impacting your low-carb breakfast choices.

- Breads: Not just limited to sweet treats, various breads, including plain white loaves, often contain added sugar, which, coupled with refined white flour, can significantly disrupt blood sugar levels.

- “Healthy” packaged foods: Don't be deceived by marketing claims — many products branded as healthy, such as granola, protein bars, gut-healthy yogurts, and gluten-free alternatives, may be laden with added sugars.

How does added sugar affect metabolic health?

Sugar in its various forms can have a very different effect on metabolic health. When you eat whole fruits, which are relatively high in natural sugar, the presence of fiber significantly influences the metabolic response. Fiber slows down sugar release and absorption minimizing blood sugar spikes.

On the other hand, fruit juice, even homemade, lacks much of this fiber since it has been mechanically stripped away. While cold-pressed or fresh fruit juice may still contain phytonutrients and antioxidants, this absence of fiber leads to faster sugar absorption and potential blood sugar spikes. Even though there may not be added or refined sugar in pure fruit juices, these drinks can still create high glucose variability that contributes to metabolic damage.

However, the worst culprits are heavily processed items like pop tarts and Twinkies, both of which lack fiber, are high in added sugar, and are devoid of nutritional value. Ultra-processed foods like these sharply raise blood glucose levels, triggering a cascade of metabolic disruptions with both short-term and long-term adverse health effects.

Studies have investigated the impact of excess added sugar consumption. In one study, young people consuming sugar-sweetened beverages at 0%, 10%, 17.5%, and 25% of daily energy requirements saw an increase in LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol), ApoB (the main protein found in LDL cholesterol), and postprandial triglycerides in just two weeks [4]. This suggests that excess sugar rapidly has a negative effect on cardiometabolic health.

In another study, individuals consuming 1 liter per day of sugar-sweetened cola for 6 months showed increased triglycerides compared to people drinking low-fat milk and aspartame-sweetened beverages [5]. Despite all groups having similar body weight gain, sugar-sweetened cola led to increased visceral fat accumulation, triglyceride and cholesterol levels. These findings highlight how added sugars harm metabolic health, going beyond the effects associated only with weight gain.

In addition to compromised markers of cardiometabolic health, regularly consuming added sugar can create significant blood glucose variability (GV). Excessive GV, beyond normal fluctuations, increases the risk of diabetic complications and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in non-diabetic individuals [6, 7]. While the exact mechanisms are not fully understood, emerging evidence suggests a connection between daily blood glucose fluctuations, improper blood flow, inflammation, and oxidative stress, contributing to blood vessel damage and atherosclerosis (a condition caused by plaque build-up in the arteries).

Aiming for stable blood sugar levels is key to avoiding the negative effects of the “glucose rollercoaster,” and eliminating added sugar is an effective and efficient approach to bring your glucose levels back into balance.

Does added sugar cause inflammation?

When your bloodstream is flooded with excess sugar due to factors like insulin resistance or a significant post-meal spike, a process known as glycation kicks in [8]. Glycation involves the binding of sugar to proteins in the body, causing these proteins to malfunction. While the body can usually manage glycation by clearing glycated proteins, an excess of added dietary sugars accelerates this process, overwhelming your system with glycated proteins [9].

This disrupts various cellular functions, causing systems in the body to become faulty and congested, ultimately leading to the production of oxygen radicals that drive oxidative stress and inflammation [10]. Oxidative stress damages cells and increases inflammation. Chronic, persistent inflammation, which can also be directly mediated by smart dietary choices, is associated with insulin resistance, disrupting blood sugar regulation and potentially escalating into more severe conditions over time.

Does too much sugar cause diabetes?

In the ongoing debate on whether excessive sugar consumption directly causes diabetes, the short answer is no. However, it is important to understand that metabolic health operates on a spectrum, and the consistent overconsumption of added sugary foods does stir up some metabolic trouble, setting the stage for high GV and insulin resistance.

Added sugars not only disrupt our brain signals, but their widespread availability also compromises our innate ability to regulate sugar intake. This unconscious overconsumption builds a heightened tolerance for sweetness and activates addictive pathways in the brain [11].

The Standard American Diet, characterized by hyper-palatable ultra-processed foods loaded with added sugars, has triggered a shift in taste preferences and cravings. In a recent randomized controlled study, participants were exposed to high-fat/high-sugar snacks for 8 weeks [12]. In this short time, alterations in brain signaling were observed, particularly in dopamine pathways, activating the same reward centers as seen in addictive patterns associated with drug use. This research suggests that regular, habitual exposure to foods containing added sugars may drive neurobehavioral adaptations, disrupting brain signaling, and in turn, increasing the risk of overeating, weight gain, and metabolic disturbances.

The more added sugar we consume, the greater the strain on our metabolic systems to restore blood sugar balance. This not only heightens the risk of type 2 diabetes but also increases vulnerability for complications such as cardiovascular diseases, obesity, cancer, and other metabolic disorders.

How to minimize how much added sugar you eat

Taking steps to minimize added sugar intake is recommended for anyone looking to optimize their metabolic health. Here are some tips for getting started:

- Decoding nutrition labels and identifying hidden sugars - When examining nutrition labels, be vigilant about identifying added sugars by scrutinizing ingredient lists. Pay attention to the added sugar amount on the label, now a required feature in the U.S. Opting for foods with a daily value percentage below 15% is a good starting point. Moreover, sugars go by various names. While familiar names like glucose, fructose, and sucrose may be recognizable, keep an eye out for sugars with names like dextran, malt powder, fruit juice concentrate, or rice bran syrup.

- Embrace whole foods - The healthiest foods with the best nutrient profiles often don't have a nutrition label. Prioritize whole, unprocessed foods rich in essential nutrients and fiber.

- De-normalize sugar - Opt for unsweetened versions of beverages (e.g., almond milk, yogurt) to sidestep unnecessary sugar consumption, and to start retraining your sweet tooth.

- Sugar reduction in recipes - Why not try reducing sugar in recipes, giving your taste buds the chance to adapt to lower sweetness levels? Contemplate whether that teaspoon of sugar is actually needed in the sauce or if the tablespoon of honey is necessary in the curry. Or, if you prefer a more savory banana bread over a sweet dessert, try cutting the sugar by half and savoring the natural sweetness of the fruit.

- Meal planning for nutrient density - Plan meals in advance to include whole, nutritious ingredients and avoid last-minute, sugary convenience choices.

Key takeaways

- Currently, all age groups consume way more than the recommended amount of sugar, and given the metabolic health crisis at the moment, reducing added sugar intake is a public health priority.

- Not all sugars are created equally - the body deals with natural sugars from fruit and complex carbohydrates very differently to added sugars in processed food.

- Added sugars are often lurking where you least expect them including soups, nut butters, breads, and products labeled as "healthy."

- Fiber in whole foods plays an important role in slowing sugar release, minimizing blood sugar spikes, while processed items without fiber can lead to sharp blood glucose spikes.

- Regular consumption of added sugar has been linked to impaired blood flow, inflammation, oxidative stress, diabetic complications, cardiovascular disease, and mortality.

- Reduce added sugar intake by scrutinizing labels for hidden sugars, opting for whole, unprocessed foods, choosing unsweetened beverages, and lowering sweetness preferences in recipes.

References:

- https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sugar/how-much-sugar-is-too-much

- https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/nutrition-facts-label-images-download

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3490437/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441807/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22205311/

- https://drc.bmj.com/content/9/1/e002032

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12933-020-01085-6

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18473850/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5409724/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4384119/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3831532/

- https://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(23)00051-7